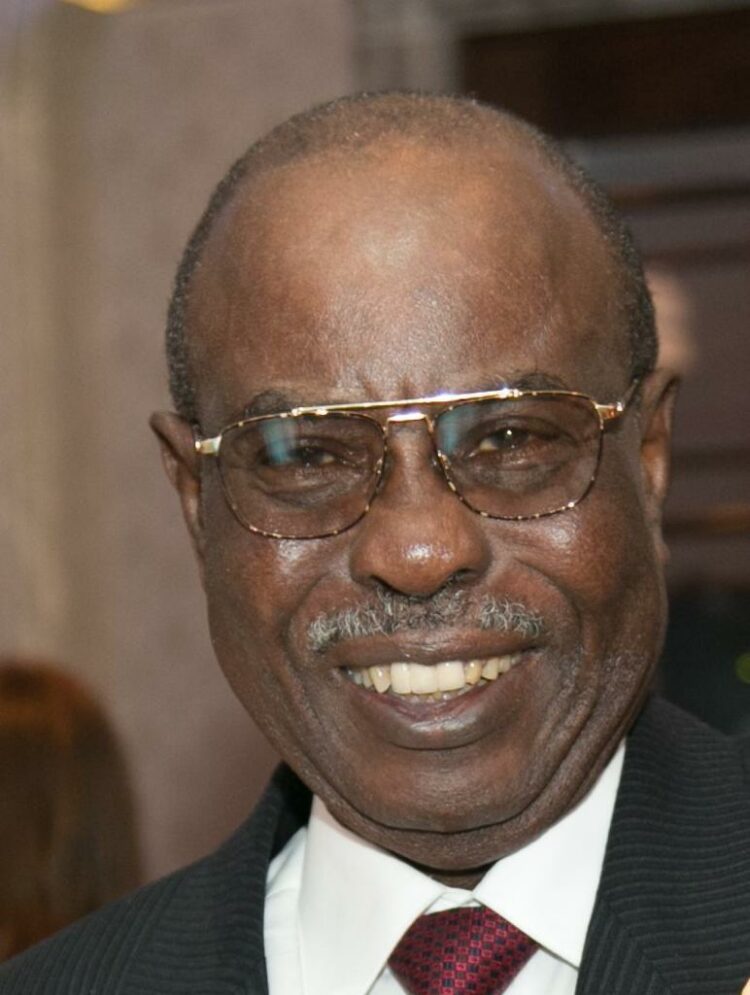

Phillip Effiong is a Professor of Drama at Michigan State University, United States of America, USA. His father, Gen Phillip Effiong was the second-in-command to Chukwuemeka Ojukwu during the civil war. In an encounter with him during a visit to Nigeria, he reminisces on the war and the post- war Nigeria, the agitations for resuscitation of Biafra, the historic and international dimensions of the war, why the full story of Biafra is yet to be told and how peace and unity in Nigeria can be attained among other related issues. He spoke with CHIDI OBINECHE.

In retrospect, how did Nigeria survive the deep socio- political upheavals of the 1960’s that culminated into a fratricidal civil war?

I don’t know that Nigeria has survived it in terms of moving forward, because I think, survival is not just existing. Survival is making progress. I don’t think we have learnt the lessons of that period or that we are even moving forward economically or politically. If you speak to most of the citizens of this country, you will realize that we are deteriorating. Things are not working out well. People do not feel safe; there seems to be a growing concern about violence especially about the fact that our security systems don’t seem to be doing anything about these problems. People are very worried about tomorrow; about basic needs; they are worried about infrastructure and think that perhaps, we are more divided than we were in the 60’s, even though the war was supposed to unite us. I don’t think that has been achieved.

What are your basic impressions of the strife of the 60’s, the events that led to them and how the resolutions came?

There was a talk I gave recently where I said that boundaries, especially with colonialism; new boundaries were created that made us very territorial. Increasingly, we became more conscious of what we own; our own states, and instead of cooperating with our neighbours, we tended to push our neighbours out of our states, and we see ourselves as controlling the political and economical resources we had in those boundaries; and that this will keep those people apart from those people who we had cooperated with in terms of trade, language, culture. And so there is a root cause of that problem and the more we fragment ourselves and believe that we can take care of ourselves and take care of our own business, the more we isolate ourselves and the more we cannot function together the way we should. Many people think that when you’re given local governments and states they have become autonomous, but we don’t realize we are balkanizing ourselves more and making us weaker. We are increasingly fragmented into smaller, weaker groups and as long as we remain weak, what other forces that come against us we are not going to withstand them; whether they are political forces, whether they are forces that manifest in the form of corrupt governments, or whether they are just violent groups. We are not equipped in our tiny units; in our weak units to withstand the challenges.

Read Also: All We Want Is Biafra, Not Igbo Presidency – Cleric Udeh

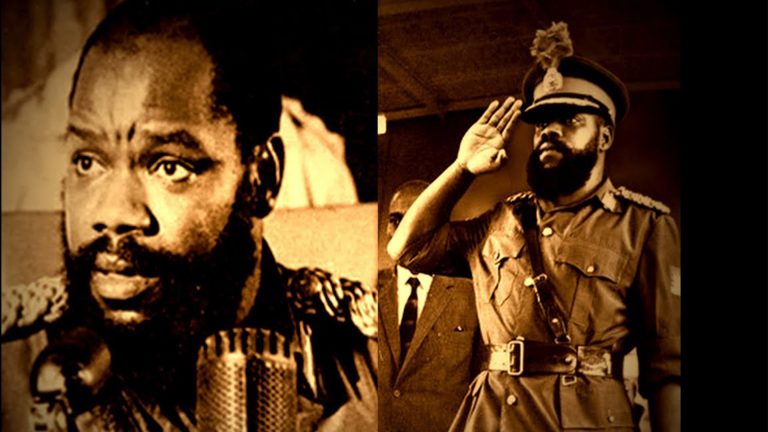

Let me talk a bit about your dad who was a top military officer in Nigeria and later became the second – in – command in Biafra behind Ojukwu. He handed the instruments of surrender of Biafra to Nigeria. What influenced his surrender speech? Secondly, were you scared he was going to be killed when he was going to do the surrender?

Well, to surrender was considered to be the right and most pragmatic decision at the time. That decision should have been made; it was agreed; in order to save lives. It has to be remembered that at this time, very little was left of what was originally Biafra. The morale was down; there was a lot of starvation. There were deaths on a large scale and the army had been weakened tremendously. Biafra had far little resources to withstand the larger and more equipped Nigerian army. So, it made sense that some kind of peaceful resolution should be pursued, and I think, this was done with a delegation. My dad didn’t just make that decision alone. Biafra was a well – structured government, and so the leadership of Biafra took that decision because he, at that time had taken over power from General Ojukwu. He led the delegation, and if you look at the surrender, the surrender was more of negotiation, requesting that our people need to be part of any new constitutional arrangements. If you look at it carefully, it was not all about surrender and submission. Of course, I feared for my father’s life. Although I was a mere boy, the war had already instilled the fear in us, with the bombings, strafing, and the deaths that were all around us. At some points we lived near refugee camps and every day people died. And so there was that sense of fear hovering over us. And when he went, quote and unquote into the lion’s den, we didn’t know whether he would come out or not. Yes, there was a lot of fear, not only at that time, but even after the war.

After the war he was detained. What was life like for him and for you, the family and relations, who were in a state of apprehension?

As a matter of fact, three days before the end of the civil war, we were among the groups of people who were living in the cargo planes, and though my mum and me weren’t physically in the country, but he was constantly receiving messages. So, we knew what was going on. There was a lot of fear, but we felt safe because we were outside of Biafra.