Fifty-six-years ago today, a woman from Ohio became the first woman to fly solo around the world.

No, you are not doing the maths wrong. I am not talking about that other, much more famous, female American aviator. I am talking about Jerrie Mock, private pilot, housewife – and my grandmother.

When she left for her round-the-world adventure, she was dubbed The Flying Housewife by the media.

She was a 38-year-old mother of three who had wanted to fly around the world since she was a little girl.

When she and her husband, Russell, discovered that no other woman had done it yet, they immediately started the process of filing the paperwork to officially seek the world record.

Jerrie and Joan

About six weeks later, however, another woman – a younger, professional pilot – attempted to file her own paperwork. That woman was Joan Merriam Smith.

Jerrie’s 750 hours of flying seemed unlikely to hold up against Joan’s thousands. Joan took off two days before Jerrie. But as Jerrie had filed the paperwork first and only one person may officially attempt a record of this kind at any one time, assuming Jerrie made it, she would be the first on record. But if Joan beat her to it, she could still take the unofficial title.

“The newspapers liked to make a big deal about the race. It wasn’t really a race,” my grandmother told me on many occasions.

In 2012, I conducted several interviews with Jerrie, asking for details that she had not included in her book, Three-Eight Charlie.

“What would you do differently, Grandma? What scenes would you add?” I asked.

“I would [show] more of what went on back home [while I was flying]. Russ talking on the phone and shouting at me wherever I was in Africa and him lying about what Joan had done,” she told me.

“She was … stuck in South America. He told me she was doing all these things – but she wasn’t. She was stuck with leaky gas tanks. He said, ‘She’s flying places every day. She’s going to beat you.’ He made me so angry I almost quit!”

Suspicions of sabotage

On March 19, 1964, Jerrie left Ohio’s Port Columbus airport in Charlie, her 11-year-old single-engine plane.

Charlie had needed some new equipment to be ready for the flight ahead. There was new radio equipment and all but the pilot’s seat had had to be removed to make way for the additional fuel tanks needed to fly over the open ocean.

Jerrie was using some cutting-edge technology. Ken Richter had recently invented the Richter gauge for detecting ice in the carburettor. “There was a tendency to get carburettor ice, and that would freeze up and the engine would quit because it couldn’t get gas,” she explained to me.

Richter sent Jerrie one of the gauges, which she had installed. But, being new technology, adjustments had to be made. “One of the mechanics there put it in … he put it [where] the old gauge [should go] and it wasn’t working. I had to go back … and they put it in the right place.”

There were several other mishaps as Jerrie prepared Charlie for the flight.

“We were flying down to Cincinnati and [Russ] was in a rush to park. He turned around quickly and hit the fence with the tail. They put a piece of metal over the tail … It didn’t look so good,” she recalled. “[A newspaper] interviewed me and Charlie and took a picture of the tail Russ had bent.”

Then there was the problem with one of the radios, and another with the oil filter.

“There were minor odds and ends that didn’t get shipped … but the oil [filter], that was the one that would really have been a problem,” she told me.

“Russ was trying to get [the plane] to swing around … and in the process … all of a sudden oil starts pouring out of the plane. They took it apart and discovered that the new oil filter had been replaced by [an] old one. If I had taken off with that, I would have been killed. That was the most dangerous thing.”

She suspected someone had tampered with it in a bid to sabotage her efforts, but with no evidence and no idea who, when she shared stories of it with her family, she referred only to “the bad people”.

Read Also: Chinese Pilot Banned From Flying After Cockpit Photo

The flight

But the preparations were the least of Jerrie’s worries. When she took off from Ohio, she had 21 stops and nearly 37,000km (22,860 miles) ahead of her. Her first leg was through the Bermuda Triangle. As she left radio range, she heard the operator say: “Well, I guess that’s the last we’ll see of her.”

“I wasn’t entirely sure he was wrong!” My grandmother often chuckled as she recounted the tale.

“I had never flown over open water before. And I was going to fly all the way around the world. But hey, I accomplished two out of three lifelong dreams. That’s pretty good for ‘just’ a woman, [as they called me].”

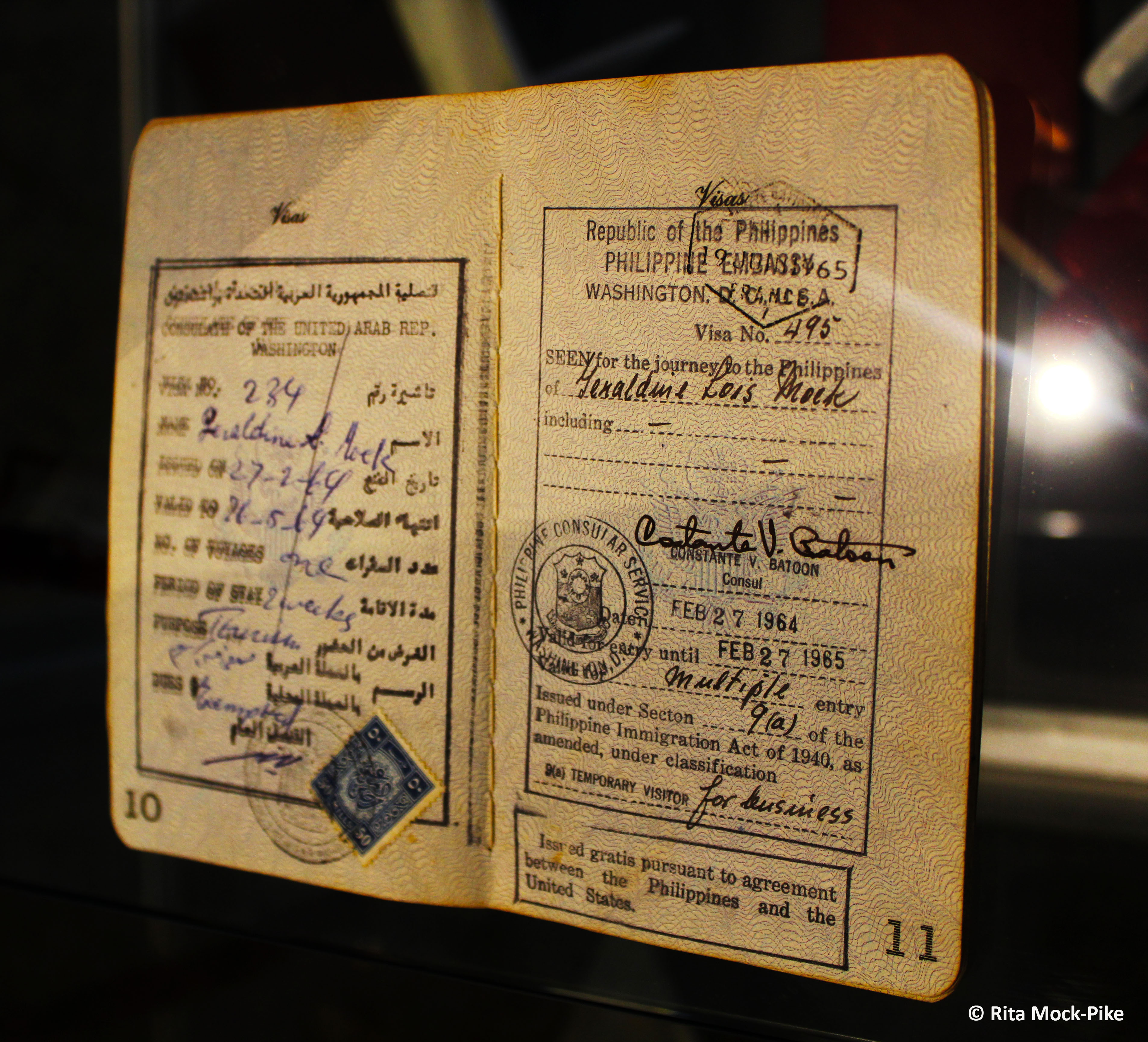

The flight took her through the Azores, North Africa, the Middle East, Asia and back through the Pacific Islands. Along the way, she encountered people who could not comprehend a woman making this journey by herself; some who opposed it and others who, although surprised, received her with open arms.

She recalled how, when she landed in Saudi Arabia, the guards sent by Prince Faisal to inspect the plane, wondered: “Where is the man?”

When a search of the cockpit turned up no one else, the hundreds of people surrounding the tarmac cheered. They paraded her around so everyone could “see the lady pilot”.

In other places, they were not so impressed. In Manila, the capital of the Philippines, she said her instructions on how to return the fuel tanks to their proper place were ignored, so they had to do it all over again. “They didn’t believe that I knew what I was talking about.”

The flight took 29 days, ending on April 17, 1964.

Twelve world records

In October 2019, Jerrie was posthumously welcomed into the Ohio Civil Rights Hall of Fame for her accomplishments in women’s rights, freedom and aviation in general. I received the award in her honour. Had she been around to receive it herself, I suspect she would have laughed and insisted she had not done anything unusual. She would often say that any woman who knew how to fly a plane could have been the one to do it.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable things about my grandmother’s accomplishments was that she did not do them for the fame and glory, or even for the walls it might break down for other women; she did it because she wanted to see the world and this was the best way she knew how.

![Jerrie in Columbus, Ohio, with Cessna P-206 – Courtesy of Rita Mock-Pike Jerrie Mock [Photo by Rita Mock-Pike]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2020/4/17/2960e483f60b4a199e372444817daf58_6.jpg)

After she made her big world flight, Jerrie was given a Cessna P-206 from the Cessna Aircraft Company. But she would have to pay so many taxes and fees that she could not afford to keep it. So Russell and some others, along with the Catholic Society of the Sacred Heart, helped Jerrie raise funds so that the plane could be transferred to the Flying Padres, a group of priests working in remote villages in Papua New Guinea.

She loaded up the aircraft, which she called Mike, and headed to Honolulu in October 1969. From Honolulu, she took off for Papua New Guinea, although she was redirected to Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

When she made it to New Britain Island in New Guinea, she handed over the keys to Father Tony. On the flight, she set several speed and distance records (no longer hers, due to technology advancements since). That was her last flight as a pilot.

Between her around-the-world flight and this last one, Jerrie had taken 12 world records.

Today, you can visit her plane, Charlie, in the Smithsonian’s companion facility at the Steven F Udvar-Hazy Air & Space Museum facility. Unless you know what you are looking for, though, you are unlikely to spot him. He is the little red and white plane hanging from the ceiling in the general aviation section.

My first memory of Charlie was a family visit there when I was a child. We saw him in storage. He was parked next to the Enola Gay – the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb, on which I leaned, unaware of the significance of the plane – as I stared at Charlie in awe.

All she needed to be

To me, Jerrie is “Grandma”, but to the female pilots I have met throughout my lifetime, she is someone who broke down barriers for them. These pilots have a role model in a woman much like themselves. Someone “normal”, someone courageous. Someone who stepped into a cockpit, saying: “I don’t care if I’m not supposed to do this. I’ll do it anyway.”

One such pilot is Shaesta Waiz, founder of Dreams Soar. She became the first certified civilian female pilot from Afghanistan and, inspired by my grandmother, the youngest woman to circumnavigate the globe in a single-engine plane. She stopped in Ohio as a nod to Jerrie.

Most pilots I have spoken to cannot imagine making a journey like Jerrie’s with the kind of equipment she had. But she was a bold woman. She fulfilled her lifelong dreams – apart from riding an elephant – and sought to inspire others to do the same.

She did not seek greatness, and, in her mind, she was not great. She pushed through her fears and disregarded society’s expectations for a suburban housewife.

“I wasn’t a great pilot. I was a competent pilot,” she told me. And that is all she needed to be.

This year’s anniversary is particularly significant for me, because I am the same age now that Jerrie was when she made her flight around the world. I had planned to take my first flying lesson on the anniversary. I was also going to launch my one-woman show portraying her on stage, and I hoped to complete her dream for me to visit more countries than she ventured to during her lifetime. With the COVID-19 quarantines and travel bans, these dreams are on hold for now, like those of many others. But once this has passed, I know what she would want me to do.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA