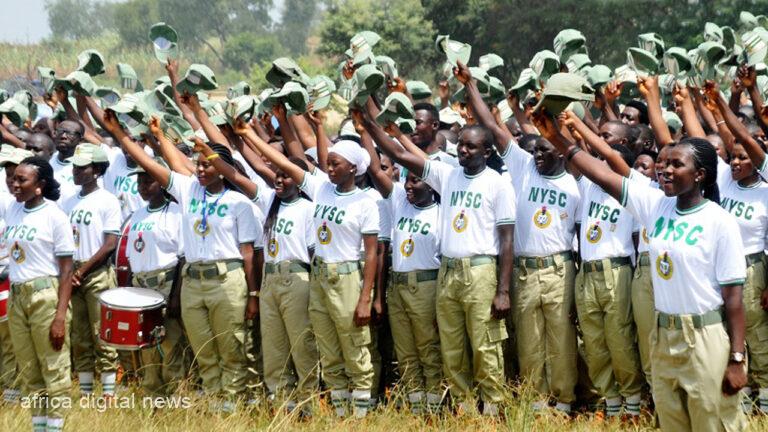

The National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) was birthed in a crucible of national crisis, shortly after the end of the Nigerian Civil War in 1973. The program, infused with the ideals of unity, reconciliation, and nation-building, sought to usher in an era where the nation’s youth could act as bridges between ethnic and cultural divides. But as we find ourselves nearly five decades since its inception, we must critically evaluate the original ethos against the contemporary realities: Is the NYSC still the bastion of national unity and service it was conceived to be, or has it morphed into a year-long hiatus that sidetracks Nigerian youth from their career paths and aspirations?

The program’s noble aims were designed for a different era, one where the physical meeting of cultures could catalyse a deeper unity among a people torn by ethnic strife. Today, however, the narrative has shifted dramatically. In a world where the concept of ‘global citizenship’ has been thoroughly embraced, the idea that moving a graduate from one state to another would induce national unity seems not just outdated but somewhat naïve.

For the thousands of graduates mobilised each year, the NYSC scheme often means a detour from their chosen career paths. While some lucky ones get placements that align with their skills and ambitions, a large number find themselves in roles that add little or nothing to their professional development. In a nation where relevant work experience often outweighs academic qualifications in the job market, this lost year can have long-term implications on the employability of our youth.

Moreover, as Nigeria grapples with a variety of security issues ranging from insurgency in the North to banditry and communal clashes in other regions, the NYSC scheme sometimes unwittingly exposes young people to undue risks. The numerous reports of Corps members being kidnapped or killed have become a grim addition to an already unappealing situation.

The Economic Cost of NYSC: A Deep Dive into the Financials

Let’s begin with the stark financial realities of the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) in the context of Nigeria’s socio-economic landscape. As a nation grappling with the challenges of high unemployment, inflation, and public debt, one must ponder the financial sensibility of sustaining a program like the NYSC, whose annual budget has skyrocketed into the billions of Naira.

According to records, the Federal Government has spent a staggering N475.2 billion on monthly stipends for corps members alone from 2020 to 2023. It’s imperative to contextualise this figure against Nigeria’s youth unemployment rate, which exceeds 40%. One then wonders, could this enormous sum be used more productively to tackle critical areas like job creation, skill development, and entrepreneurship?

Read Also: Is Nigeria Not Tired Of Wasting Money On The Futile NYSC?

Further dissecting the numbers reveals more staggering facts. The scheme, which mobilised at least 300,000 corps members yearly in recent times, costs the government N396,000 per corps member annually. When calculated, it translates to an expenditure of N118.8 billion per year. If some analysts’ projections hold true—that the NYSC will consume nearly N3 trillion in the next five years—the financial implications for a struggling economy become even more alarming.

Additionally, NYSC budgets reveal astonishing amounts spent on operational costs. For instance, in 2017, the NYSC budget showed an expense of N2.49 billion for the kitting of 297,293 corps members and N3.27 billion for meals during the 21-day orientation. These figures exclude the costs of camp maintenance, logistics, and the overhead for running the scheme. Clearly, the economic burden is significant and raises the question: Could these resources be allocated in a way that directly contributes to the economic development of Nigeria?

It’s also worth noting that these figures do not even encapsulate the contributions from state governments. For example, Lagos State budgeted N300 million to support NYSC interns in 2020. This multiplicity of expenses from both federal and state levels further amplifies the economic weight of the scheme.

We must also remember that these funds come from taxpayers, many of whom struggle with the high cost of living exacerbated by inflation and other economic headwinds. In a country where the price of household items, food, and transport fares have escalated significantly, it’s essential to interrogate whether the NYSC is a judicious use of limited public funds.

NYSC was initiated with the noble intent to ‘reconstruct, reconcile and rebuild the country’, Yet, as the program turns 50, the financial facts and figures lay bare an urgent need for a comprehensive reevaluation. The financial cost of running the NYSC appears unsustainable and demands that we ask if these funds could be redirected to initiatives that offer a more tangible impact on the nation’s economic health and the future of its youth.

Indeed, as we reflect on the billions spent annually on this program, we must ask: Is the NYSC an investment in the future, or has it become a financial albatross that the Nigerian economy can ill afford? The time for a financial reckoning of the NYSC has arrived, and the economic data is the ledger upon which its future should be judged.

The Opportunity Cost for Youth

As the world shifts towards a more dynamic and skills-oriented economic landscape, the significance of timely work experience and skill acquisition for young professionals cannot be overstated. In this light, it’s crucial to examine the opportunity cost of the mandatory one-year National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) program for Nigerian youth.

Firstly, let’s clarify what ‘opportunity cost’ implies in this context. It refers to the value of the best alternative forgone when a decision is made. For thousands of young Nigerians fresh out of universities, the NYSC year translates to 12 months where they could have gained specialised work experience, enrolled in advanced courses, or even started their own ventures. Instead, they find themselves serving in often remote locations, engaged in activities scarcely related to their career ambitions.

Consider the mismatch of skills and postings that many corps members face. A graduate in Computer Science may find themselves teaching basic arithmetic in a rural school, while a Civil Engineering graduate might be coordinating immunisation drives in a community. While these are noble activities, they are not necessarily aligned with the career paths these young people intend to follow. In industries like technology, healthcare, and finance, where advancements occur at breakneck speed, a year’s gap can make a significant difference in one’s employability.

In more developed economies, the year after graduation is a critical period for professional development. It’s a time for internships, entry-level positions, or postgraduate studies—each a stepping stone to future career advancement. In Nigeria, however, this crucial year is often spent in roles that do not add substantial value to career-relevant skills or work experience.

Furthermore, the program’s rural focus, although well-intended for even development, means that many young professionals are cut off from the urban networks and resources that are vital in the modern job market. Networking events, career fairs, and other professional development opportunities are usually based in cities, making them inaccessible for those serving in remote areas.

And then there’s the mental toll. The uncertainty and lack of career progression during the NYSC year can lead to frustration and demotivation, factors that are not conducive to professional growth.

In a rapidly globalising world, Nigerian youth are not just competing with their peers within the country; they are vying for opportunities on a global scale. Every year spent in activities not directly contributing to their career goals is a year that their international counterparts use to forge ahead.

So, as we debate the economic costs and benefits of the NYSC, we must also account for these lost opportunities for Nigerian youth. Is the program equipping them to be competitive in today’s global job market, or is it a relic of the past, holding them back from reaching their full potential? As we consider reforms or alternatives to the NYSC, the opportunity cost for the youth should weigh heavily in the balance. After all, they are not just the future of Nigeria; they are its present.

Inefficacy in National Integration

In the decades since its inception, the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) has been hailed as a linchpin for national unity, aimed at dispersing youths across different states and ethnic divisions to foster a sense of shared Nigerian identity. Yet, as the years have passed, mounting evidence suggests that the NYSC’s role in achieving its primary objective of national integration has been far from effective.

One of the most startling statistics comes from a 2019 study published in the Journal of Education and Practice. According to the research, a meager 5% of the NYSC participants believed that the program had successfully achieved its goal of integrating the nation. This alarming figure calls into question the efficacy of the NYSC as an instrument of national cohesion and begs us to reconsider its merits in contemporary Nigerian society.

While the program mandates that youths serve outside their states of origin, often in communities with cultures distinct from their own, it’s worth noting that these postings rarely result in permanent relocations or substantial cultural integration. After their service year, a significant majority of corps members return to their native regions, essentially negating the program’s integration intent. The experience becomes, at best, a brief sojourn into another way of life, rather than a transformative experience leading to a more integrated nation.

Moreover, the fleeting nature of the NYSC program offers limited opportunities for meaningful engagement with host communities. The one-year stint often doesn’t provide the depth of experience needed to truly understand and appreciate the culture and lifestyle of another ethnic group. A common criticism is that corps members, knowing their time in these communities is temporary, do not invest in meaningful relationships or endeavors that could contribute to mutual understanding and long-term integration.

Critics also argue that the program’s focus has shifted over time. In the contemporary context, the NYSC often serves as a de facto job placement service, albeit a poorly targeted one, rather than a platform for national unity. As a result, many youths view the program as a necessary but frustrating rite of passage to employment rather than as an opportunity for cultural exchange and national service.

If we are to address the underlying ethnic and regional tensions that continue to fragment Nigeria’s social fabric, it is critical to scrutinise the efficacy of institutions designed to mitigate these divides. The NYSC, despite its noble intentions, appears to be falling short of its foundational goals. While some argue that reforming the program could improve its outcomes, the existing data suggest that a more radical reevaluation is necessary.

The stark reality is that the NYSC’s original aim of fostering a united, integrated Nigeria has not been met. As the country grapples with complex challenges—from economic inequality to rising insecurity—the continued inefficacy of the NYSC in achieving national integration serves as a missed opportunity in Nigeria’s quest for unity.

As policymakers ponder the future of the NYSC, the issue of its effectiveness in promoting national integration must take centre stage. With billions of Naira spent annually, it is time to ask: Is the NYSC still a viable tool for unity, or has it become an antiquated program whose inefficacies we can no longer afford to overlook?

While the founding vision of the NYSC was noble and relevant for its time, it has increasingly become a square peg in a round hole, out of touch with the dynamics and exigencies of modern Nigeria. It’s high time is reevaluated whether the scheme still serves the purpose for which it was created or whether it has become a detour, a deviation—a wasted year in the life-journey of our young people. The answers to these questions could inform a much-needed reform or the discontinuation of a program that, while iconic, may have outlived its usefulness.

To be continued…