Till date, all the victims of Hitler in the 2nd World War are still being compensated, and looted artifacts are still being returned. Many victims of the Holocaust are still being apologised to, why then are Africans the only ones who are constantly being reminded that they should forgive and forget?

The days of colonialism were quite crazy. Colonialism which is the practice of one country assuming partial or full political control of another country and occupying it with settlers for purposes of profiting from its resources and economy is quite difficult to distinguish from imperialism. Since both practices revolve around a system that guarantees political and economic control of a dominant country over a vulnerable territory, then colonialism and imperialism actually flow along the same path.

Going down memory lane, it will be recalled that from ancient times to the beginning of the 20th century, powerful countries in the world, mostly of European origin openly scrambled to expand their influence through colonialism. By the outbreak of World War I in 1914, European powers had colonised countries on virtually every continent. Today, while colonialism is no longer so aggressively practised, its consequences and bruises are still quite evident in the lives of its victims.

Almost a century after the official end to colonial conquest in Africa, the continent has remained poor. Despite being naturally blessed with resources such as gold, diamonds, oil, natural gas, copper, and uranium, Africa is still struggling to make ends meet.

Countries like the United Kingdom committed heavy atrocities under the guise of colonialism in Africa. They stole, looted, and pillaged the continent’s resources without remorse. Despite several calls for some restitution or compensation, the UK has simply paid deaf ears.

Last year, following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, several conversations about this realities were opened. Her passing sparked another match in the ever-burning fire and returned the calls for reparations to the front burner. The nature of the conversations clearly showed that Africa’s disdain for the British royals was much deeper than it appeared and this has nothing to do with envy but everything to do with the deep pains which were inflicted on them by the former colonialists.

Read Also: Africans Must Destroy Their Inferiority Complex

The British monarch’s passing was able to revive a sensitive debate over Africa’s colonial past, the return of stolen jewels from African soil, or ‘looted’ as the Europeans like to call it. In particular, people have been calling for the return of the Koh-iNoor diamond, which is set in the crown of the queen and is part of the crown jewels on display at the Tower of London and the Great Star of Africa, set in the sovereign’s sceptre, which is also part of the crown jewels.

The Koh-i-Noor is one of the largest cut diamonds in the world, coming in at just over 105 carats. It is said to be worth between $140 million and $400m but is also hailed as priceless. It is also known as one of the world’s most controversial diamonds. This precious stone was mindlessly stolen from Africa by the United Kingdom during colonial days.

Calls have also grown for the Great Star of Africa – also known as Cullinan I and First Star of Africa – to be returned. The British have continued to shamelessly claim that it was given to them as a symbol of friendship and peace, yet it was during colonialism. The British was so brazen and mindless that they had to replace the name The Great Star of Africa with the name of the owner of the Premier Mine, Thomas Cullinan.

In recent times, European countries have come under intense pressure to reckon with their colonial histories, atoning for past crimes and returning stolen African artifacts held for years in museums in London and Paris. What countries like the UK must be reminded of is that this restitution surely goes beyond returning a few paintings and artefacts here and there. It must involve the return of all the resources which were stolen from the continent.

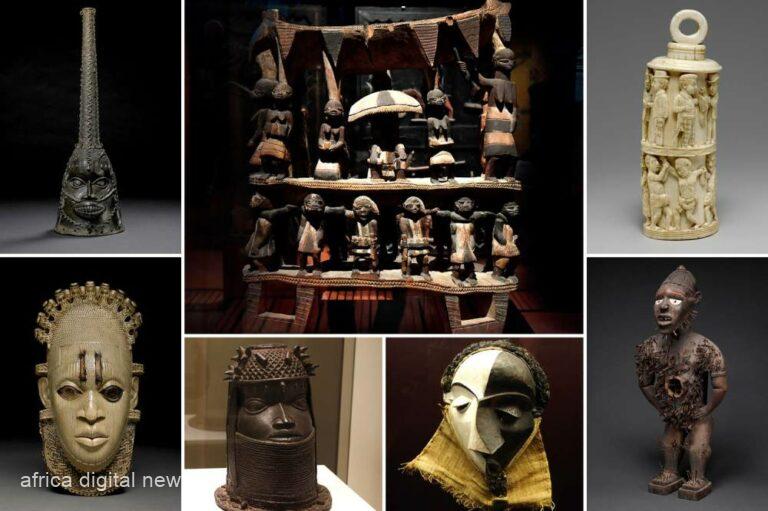

As part of recent reparations for the past, Nigeria and neighbouring Benin have seen the return from Britain and France of the first of thousands of artefacts plundered during colonial times. Nigeria’s Benin Bronzes of the 16th to 18th-century metal plaques and sculptures were looted from the palace of the ancient Benin Kingdom and ended up in museums across the US and Europe.

Till date, several billions of pounds that were siphoned from Africa by corrupt former leaders in active collaboration with British leaders remain stashed in several bank accounts across the country. Although Nigeria has arguably been the most successful among African nations in securing the return of stolen money, it has recovered only a fraction of what remains in the United Kingdom.

Not so long ago, Nigeria was forced to take legal action against the UK National Crime Agency, after repeated delays to the return of money taken out of the country in the 1990s by former dictator General Sani Abacha. However, the court case has only revealed the scale of the challenge before Nigeria. Abacha is believed to have siphoned off up to $5bn to the West. This particular case in question concerned just £150mn.

Granted that given staggering levels of corruption across Africa, there has been very valid concerns as to whether funds returned to the continent will be properly deployed and not stolen again. However, those who hold this view forget that it was actually through Western jurisdictions that the money was laundered in the first place. The truth remains that, not trusting Africans to spend their own money properly echoes the argument that the people in the continent cannot be trusted to look after our own cultural heritage, and this formed part of the reasons why the British even colonalised them in the first place.

In the case of both looted cultural heritage and stolen assets, western museums and authorities largely seem to agree that the loot should, in principle, be handed back. However, the technicalities of repatriation leave plenty of room for maintaining the status quo.

Museums say that treasures should be returned if it can be proved that they were looted. Of course, they argue, it is a different matter if artifacts were acquired through purchases and other legitimate means. But it is the same museums that are responsible for assessing the provenance of artifacts. They have a vested interest in keeping them, encouraging a lackadaisical approach and murky criteria.

Going forward, King Charles and every member of the British government must and should be pressured to do the ethical thing and return precious jewels that were stolen by British soldiers during colonialism. They must return the millions of barrels of crude oil that were siphoned from Africa. They should and must return every stolen item in their possession to their rightful owners.

These very jewels, which not only adorn the King’s crown but also fill museums across the UK, must be returned to Africa. This is non-negotiable.

It baggars belief why Britain has never been hauled to African courts to face the music for their role in crimes against humanity during the dark days of colonialism.

The present crop of African leaders must now start taking the outpouring of anger from many individuals whose ancestors were brutally erased from the map seriously. They must start prioritising the legitimate cries of people whose resources were mindlessly looted. The era of British sanctimony must be put on hold until the right things are done.