Voters in Guinea on Sunday kick off a string of elections in West Africa when they go to the polls under a cloud as the octogenarian incumbent mounts a controversial third-term bid.

Millions more will vote across the region — in Ghana, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso and Nigeria — before the year is out, under the wary eye of defenders of democracy.

“For those of us watching democracy in the subregion… these are trying times,” said Kojo Asante of the Ghana Center for Democratic Development.

Military overthrows for which the continent was notorious in the first decades after independence in the 1960s have given way to “much more sophisticated, cleaner and more cosmetic” coups, a Dakar-based think tank wrote in a recent report.

More often, power changes hands through electoral or constitutional coups featuring fraud or basic law overhauls, the Afrikajomcenter report said.

The incumbent presidents of Guinea and Ivory Coast have succeeded in pushing through constitutional changes allowing them to stand for a third term, sparking deadly unrest while adding their names to a long list of leaders with similar playbooks since 2000.

Even in Senegal, often called West Africa’s most stable democracy, President Macky Sall has been coy over his intentions with four years left in this second five-year term.

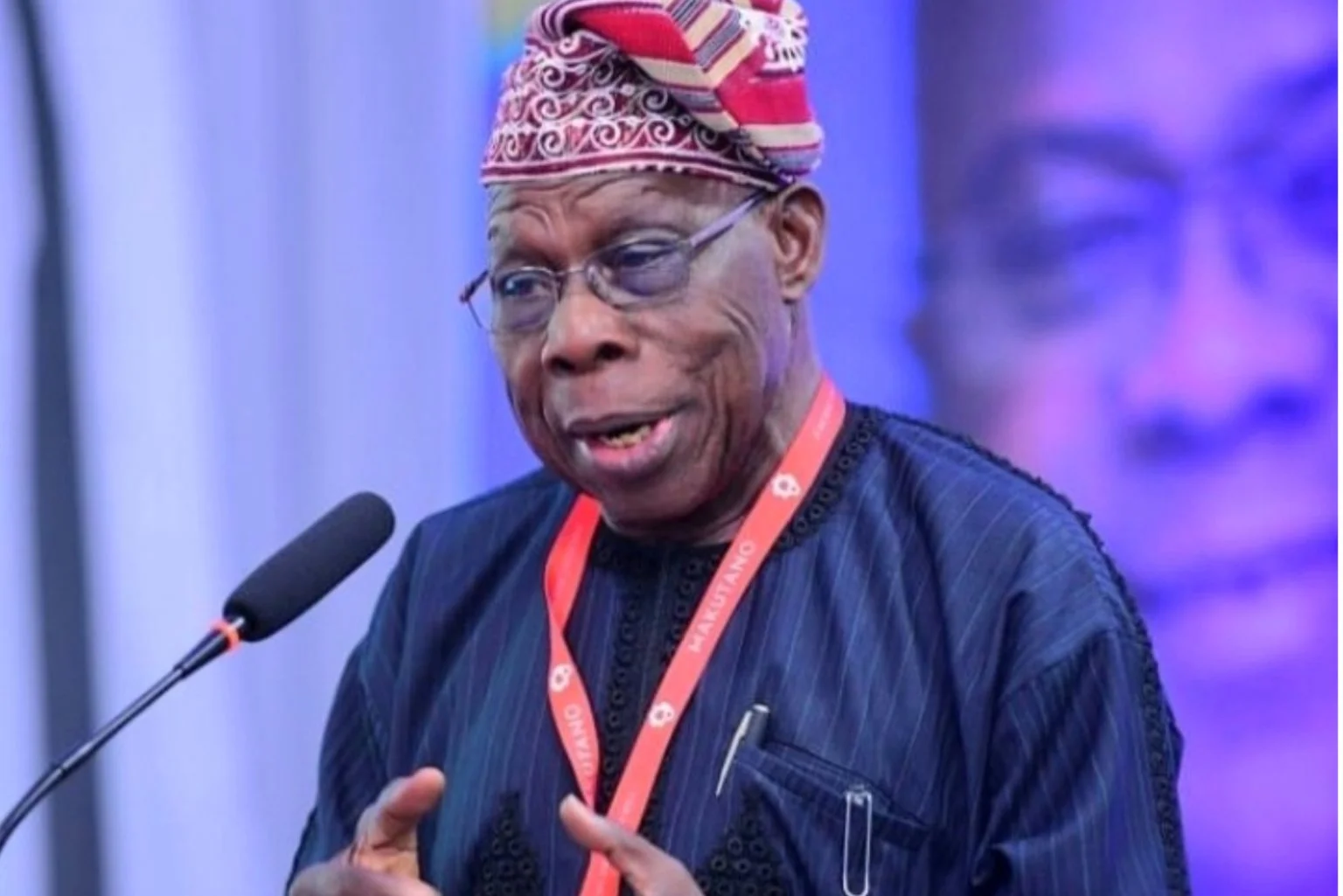

Guinean President Alpha Conde has pushed back on the notion that his third-term bid is a power grab.

“I fought for 45 years (against authoritarian regimes), I was an opposition leader,” he said on French radio RFI recently.

“It’s extraordinary that I am considered an undemocratic dictator. How can you say coup d’etat when the new constitution was adopted by referendum?”

A standout exception is Niger’s President Mahamadou Issoufou, who has been hailed for his decision to step down after two terms to allow a successor to be elected on November 22.

Ghana too can boast several peaceful transfers of power since 2000, and looks set to bolster this record when it votes on December 7, despite some concern over attacks on journalists.

But elsewhere the picture is far bleaker.

A bloodless coup in Mali ousted elected president Ibrahim Boubacar Keita on August 18, and the junta — with broad popular support — appears to be stacking the transitional government with military men.

Recent democratic gains in Liberia and Sierra Leone after their civil wars, as well as in The Gambia and Guinea-Bissau, remain fragile.

And jihadist violence and inter-ethnic fighting undermine democracies in countries from Burkina Faso and Mali to the giant Nigeria, alarming rights groups and the international community.

‘Democratic backsliding’

“We see democratic backsliding in several respects in West Africa,” said Mathias Hounkpe, a political scientist at the Open Society in West Africa (OSIWA) foundation.

“Especially in French-speaking countries, we see stricter criteria for creating parties, (and) standing in elections is becoming more and more difficult, like in Ivory Coast and Benin,” Hounkpe said.

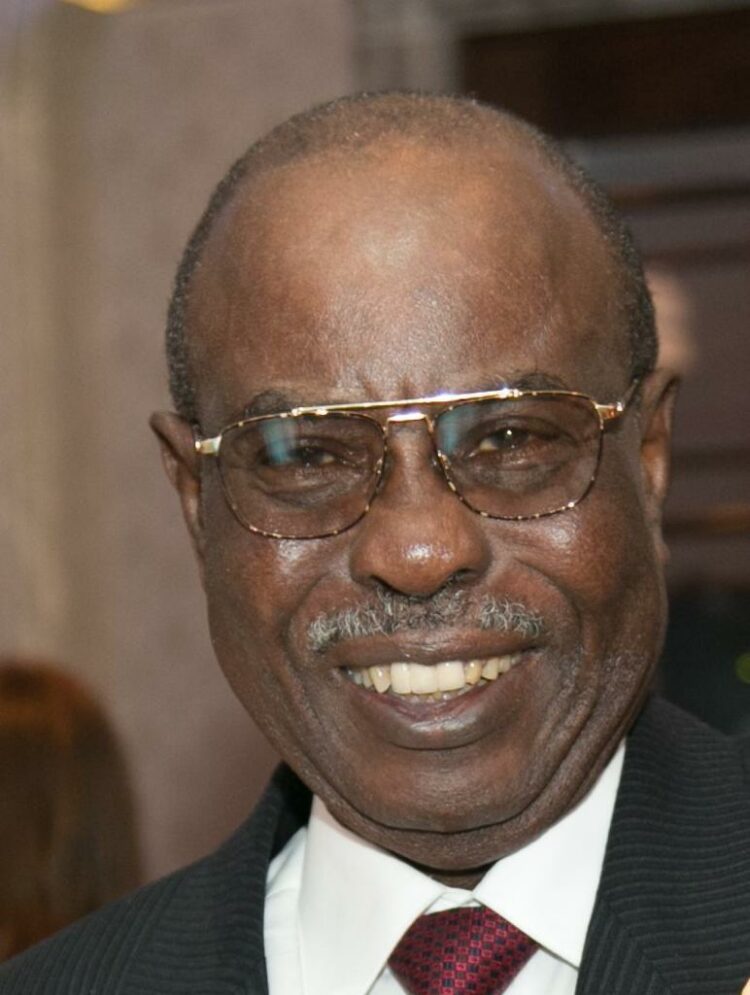

Alan Doss, who served as a UN special envoy to several African countries and is now with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, said that “over the last two decades, West Africa has led Africa’s transition toward democracy”.

“Unfortunately, what too often followed elections in West Africa has been a disappointment,” he wrote in a recent op-ed.

Doss cited unfulfilled campaign promises, grinding corruption, impunity and bad governance.

The reasons abound: economic difficulties, demographic pressures, lack of institutional counter-balances to power and an erosion of the influence of traditional mediators.

What is more, Doss said: “Today the old models of democracy, like the United States and Britain, are weakened, while non-democratic countries have gained in power like China, Turkey and Brazil.”

Big regional institutions like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the African Union “should play a much greater role, a mediation role,” said Arsene Brice Bado of the Abidjan-based Centre for Research and Action for Peace.

But both ECOWAS, which has 15 member states, and the continent-wide AU are widely seen as being of limited efficacy.

“I don’t know how focused the leaders are to deal with the challenge — a lot of the key ones are distracted,” said Asante at the Ghanaian think tank.

Guinean opposition figure Faya Millimono took the criticism a step further, telling reporters he viewed ECOWAS as a “union of heads of state”.

The body, hampered by internal dissensions, has been unable to confront the Guinean and Ivorian presidents over their third-term ambitions.

When it tried to intervene over the coup in Mali, calling for a return to constitutional order, ECOWAS was up against massive popular support for the putschists.

Malians denounced the mediators for wanting to perpetuate discredited systems, suggesting that some of the region’s leaders were looking out for their own fates.

‘All is not lost’

Some observers say West Africa compares favourably to Central Africa, which holds records for presidential longevity — in Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of Congo and Cameroon.

Rights groups point to the emergence of citizens’ movements and the improving prospects enjoyed by women and young people.

“The fact that there are elections and stakeholders (notably opposition politicians) would like to enforce the rules and play to the rules of the game, there is hope,” said Samuel Darkwa of the Accra-based Institute of Economic Affairs.

AFP