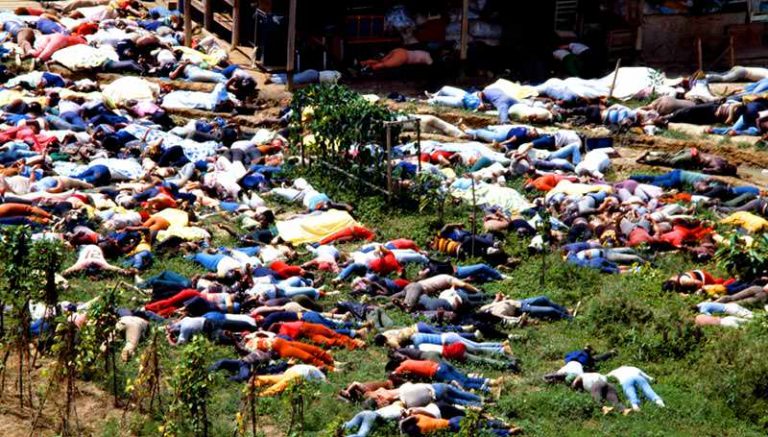

Judith Ariho does not shed any tears as she recalls the church massacre in which her mother, two siblings and four other relatives were among at least 700 people who died.

Exactly 20 years ago, in south-western Uganda’s Kanungu district, they were locked inside a church, with the doors and windows nailed shut from the outside. It was then set alight.

Two decades on, the horror of the event is still too much for Ms Ariho, who appears to only be able to cope with the trauma by closing herself off from the emotion.

The dead were members of the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God – a doomsday cult that believed the world would come to an end at the turn of the millennium.

“The end of present times”, as one of its books phrased it, came two-and-a-half months later, on 17 March 2000.

Read Also: Uganda: Injectable HIV Treatment To Kick Off Next Year

Twenty years later, no-one has been prosecuted in connection with the massacre and the cult leaders, if they are alive, have never been found.

Everything was covered in smoke, soot and the stench of burnt flesh. It seemed to go right to your lungs”

Anna Kabeireho, who still lives on a hillside that overlooks the land that the cult owned, has not forgotten the smell that engulfed the valley that Friday morning.

“Everything was covered in smoke, soot and the stench of burnt flesh. It seemed to go right to your lungs,” she recalls.

“Everybody was running into the valley. The fire was still going. There were dozens of bodies, burnt beyond recognition.

“We covered our noses with aromatic leaves to ward off the smell. For several months afterwards, we could not eat meat.”

Kanungu is a fertile and peaceful region of green hills and deep valleys, covered in small farms broken up by homesteads.

The journey down into the valley that was once the headquarters of the Movement has to be taken by foot.

From down there, it is easy to see how the religious community would have maintained their lives away from the eyes of neighbours.

Birdsong bounces off the hills and there is the sound of a waterfall in the near distance. It is the ideal setting for a contemplative existence.

But nothing remains of the building that was doused in petrol and set alight. At the edge of the spot where it stood is a long mound of soil, the only marker for the mass grave in which the remains from the inferno were buried.

Defrocked priests and nuns

The faithful had been drawn by the charismatic leaders Credonia Mwerinde, a former bartender and sex worker, and ex-government employee Joseph Kibwetere, who said that they had had visions of the Virgin Mary in the 1980s.

They registered the Movement as a group whose aim was to obey the Ten Commandments and preach the word of Jesus Christ.

Christian icons were prominent in the Movement’s compound and the cult had tenuous links to Roman Catholicism with its leadership dominated by a number of defrocked priests and nuns, including Ursula Komuhangi and Dominic Kataribabo.

Believers lived mostly in silence, occasionally using signs to communicate.

Questions would be sent to Mwerinde in writing. Known as “the programmer”, she is said to have been the mastermind behind how the establishment run, and would write back with answers.

Ms Ariho, 41, joined the Movement with her family when she was 10.

Her widowed mother was struggling to raise three children, one of whom suffered from persistent headaches. Kibwetere’s group offered prayer and a sense of belonging, she says.

The self-sustaining community would take in whole families, providing for their every need. The members grew their own food, ran schools, and used their skills to contribute labour.

We did everything possible to avoid sin. Sometimes, if you sinned, they would command you to recite the rosary 1,000 times”

Ms Ariho’s family hosted a branch of the church with about 100 members in their compound, 2km (1.2 miles) outside the town of Rukungiri.

“Life rotated around prayer, although we also farmed,” she says.

“We did everything possible to avoid sin. Sometimes, if you sinned, they would command you to recite the rosary [an entreaty to God] 1,000 times.

“You had to do it, and also ask friends and family to help, until you had served your punishment.”

Devotion to the Movement regularly involved pilgrimage to a steep, rocky hill nearby. After a tough hike through a eucalyptus forest, hanging onto rocks and grabbing at tufts of grass, the faithful would reach a rock that they believed depicted the Virgin Mary.

As we walk through her village, she points to the homesteads of the immediate neighbours. “Over there, they lost a mother and her 11 children, and in that home, a mother and her eight children died too,” she says, shifting her gaze to the ground.

Ms Ariho had not travelled to Kanungu as by 2000 she had married into a family who were not part of the Movement.

But she remembers that the leaders had an omniscient grip on the faithful, saying that Mwerinde and Komuhangi seemed to be aware of every sin that had been committed in the far-flung outlets of the church.

When a follower broke the rules, the two women would shed tears of blood, she says.

But it appears that the cult leaders may have also engaged in murder and torture before the final massacre.

In Kanungu, there are numerous wide and deep pits where dozens of bodies, thought to have been dumped over several years, were retrieved days after the blaze.

At the back of what seems like a ruined office building are two more pits, said to have been torture chambers. Pits were also found near other branches of the church.

What turned ordinary members of society into murderous cult leaders is still not clear.

Before his apparitions, Kibwetere had been a successful man, and a regular member of the Roman Catholic community.

Topher Shemereza, now a local government official, saw him as a father figure.

“He was an upright member of the community and a shrewd businessman. I did not have a job when I finished university, so he offered me a deal to transport local moonshine, which we sold in the neighbouring districts,” he explains.

A few years on, Kibwetere informed his protégé that he would no longer sell alcohol. The older man and his fellow cult leaders spent a fortnight in Mr Shemereza’s government-issued house right up until the night they set off for Kanungu, where they would establish the Movement’s headquarters.

“That was the last time I ever saw him. The man I knew was not a murderer. Something must have changed in him,” he says.

After the Movement’s foundation, word of Kibwetere and his religion spread across south-west Uganda and beyond.

The community was not closed off from the rest of society, and several people in positions of authority – including policemen and local government officials – were aware of its activities. But little action was taken against the cult before the inferno.

Although Interpol issued notices for the arrest of six cult leaders in April 2000, it is still not known if any of them died in the fire or whether they are living in hiding.

A 2014 Uganda police report indicated that Kibwetere may have fled the country. But others doubt that he was well enough to do this.

No memorial

Spiritual movements that bear the hallmarks of the Kanungu cult, where devotees unquestioningly believe their pastors can resurrect the dead or that holy water will heal ailments, have continued to emerge across the continent.

The Kanungu cult pointed out the evils of the time… and preached a renewal or re-commitment to the faith”

Their appeal is clear, according to Dr Paddy Musana of Makerere University’s Department of Religion and Peace Studies.

“When there is strain or a need which cannot be easily met by existing institutions like traditional faiths or government, and someone emerges claiming to have a solution, thousands will rally around them,” he tells the BBC.

“The Kanungu cult pointed out the evils of the time… and preached a renewal or re-commitment to the faith.”

Dr Musana adds that one need not look too far to find a similar thread in the messages of today’s self-proclaimed prophets.

“The ‘Jesus industry’ has become an investment venture. Today’s preachers talk about health and wellness, because of the numerous diseases, and a public health system that barely functions,” says the academic.

He argues that the government needs to do more in overseeing these spiritual movements.

Two decades on, the 48-acre plot at Kanungu is now being used as a tea plantation, but local businessman Benon Byaruhanga says he has plans to turn parts of it into a memorial.

So far, the dead at Kanungu have never been officially remembered. Those who lost family members have never got any answers.

“We pray for our people on our own. We bear our pain in silence,” Ms Ariho says, reflecting on the deaths of her mother and siblings.

BBC NEWS